Commerce. Hubbub. The noisy marketplace. The tens, hundreds, and thousands of small exchanges. In the store, online, over the phone, from an airplane. It’s like an ecology, the ecology of the economy. The creation and shifting of resources from one area of the ecology to another. All voluntarily. All based on what we value, on what we think is worth the expending and spending of resources. The values, where do they come from?

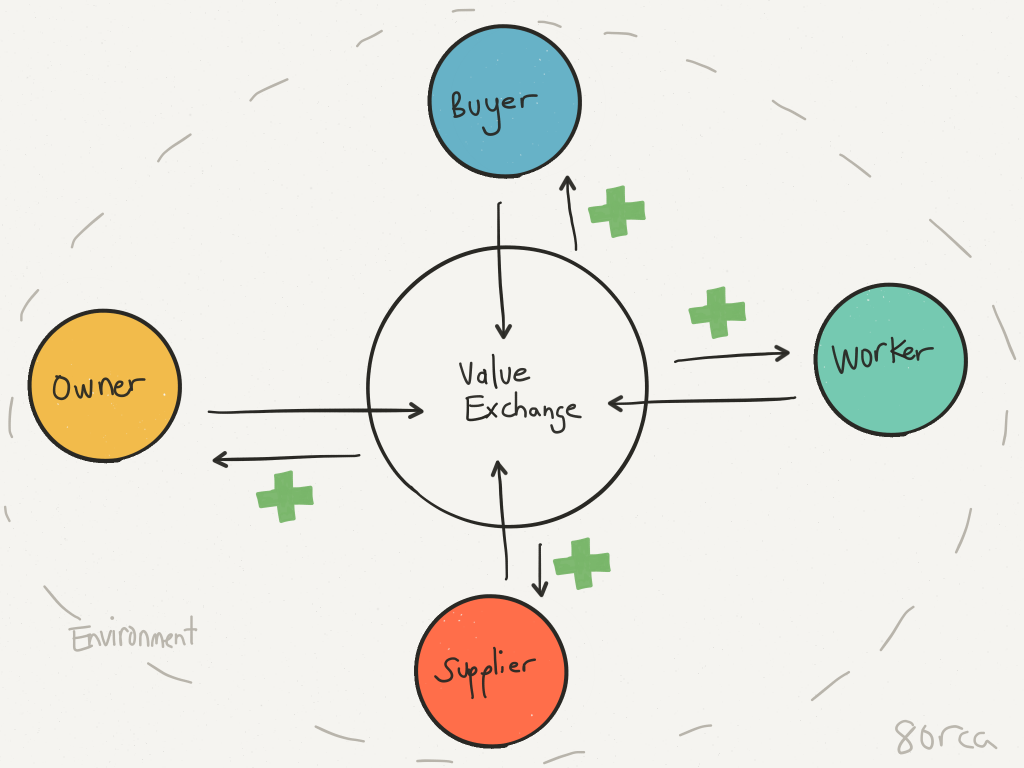

As entrepreneurs, we design “the value exchanges:” those interactions that bring together buyers, workers, suppliers, owners, and indirectly, their surrounding environments. If we’ve done our job well, each party leaves the exchange with greater value than they brought to it. In a very real sense, they are affirmed in that value through their interactions with the others. The whole process is a way of cooperating to make the imaginary real, the potential actual, the unseen seen. It also transcends the laws of matter: while the physical matter doesn’t increase, paradoxically the whole enchilada just grew, because it grew in a non-material dimension: in the minds and souls of the participating parties.

“The value exchanges” are preceded by a decision, and the savvy entrepreneur is really a decision architect. She’s created the exchange, but the decision is what gets the movement of the exchange activated. Architecting that decision is really a matter of leadership, of presenting the decider with their freedom. The frame of the decision proposes a truth about reality, what makes reality better, and how the exchange brings about that reality.

Every business is a hypothesis, or really two hypotheses: (1) an economic hypothesis, and (2) a human hypothesis. The economic hypothesis is a claim: that we can create more economic value than we consume. The human hypothesis is also a claim: that what we’re doing is good for the human person. In this way, every business is not only a hypothesis, it’s also a statement of belief: that what we’re doing creates value and is good for people. It’s why I think it’d be wise for every business to have an anthropologist on staff, or at least someone who asks questions about what it means to be human, what makes for better humanness, and how what we do contributes to that end for our customers.

Businesses can survive for a while on cheap sales: hyping product promises based on a vision of reality and definition of a human being that leads to purchases, but the truth always comes out in the end (although sometimes it can take generations for it to come to light). The best long-term strategy is to propose the good, and encourage people to direct their resources to what should truly be valued. Here we find the business owner who asks more than the question of what people will spend a buck on, but searches for what really makes a positive difference and helps. He explains it over and over again, one person at a time. He realizes that the existence of his business depends on a set of customers also sharing that belief, and that his enterprise is a bullhorn for that belief.

“The value exchanges” are actually “values exchanges” — manifesting what we think is important through the design of the business model. And in this way, business becomes a moral enterprise.

(As originally posted on the Thriveal blog.)